Previously: Grief, sort of, caught up with me at the Iranian Interest Section in DC. But then a layover in Frankfurt and a defiant stranger with champagne, cracked open the door to a long-forgotten part of myself.

Read the previous post by following the link below.

I went to work the next day, asked Don for two weeks off, and bought a one-way ticket to DC, hoping to renew my passport as quickly as possible.

My father, in the meantime, had had his quadruple bypass with my mother and brother at his side. Unfortunately, he’d had a stroke during the operation, and things had gone from bad to worse. I was desperate to get to him, but I had no idea how long the passport renewal process would take.

The day I put on my hijab and went to plead for a rushed renewal, I was escorted into a small side room off the main hall of the Iranian Interests Section in D.C. Iran hasn’t had an embassy in the U.S., since the revolution in 1979—so consular affairs are handled through a wing of the Pakistani Embassy.

I teared up as I spoke to the consulate officer and somehow moved him enough to take action. He promised to expedite my paperwork.

What I remember most from that meeting isn’t relief, but a quiet grief—grief over the fact that, even as I meant it, I still had to perform care for my father.

There are people who feel love for their parents easily. For others, love lives in more complicated terrain. In my case, the love was there—but so were fear, resentment, and distance. My father didn’t always know how to show care in the moments I needed it most. When I was eight and hospitalized after a car crash, he visited only once—stood at a distance, detached, and never touched me. When I had paratyphoid at fourteen, a kind neighbor appeared at my bedside, but my father only cracked the door open, gave a silent smile, almost afraid to enter, and disappeared.

He was a man of contradictions—an ethical human with a deep capacity for sweetness, but at home, he often held his love at arm’s length. I’d be lying if I said I knew why he was the way he was. He seemed to move through life trying to keep his own tenderness in check, as if emotion itself were a liability. I think it was more complicated than patriarchy or the usual expectations of masculinity. He was singular and defied so many norms. And there were men around me who’d broken the toxic masculinity mold.

And yet, of all the people in the house, he was the one who understood me best. Not often, not loudly—but in rare glances, stray sentences, small gestures that said, “I see you.” They were infrequent, but they were lifelines.

So yes, my feelings about going to Iran to tend to him were complicated but he was also the father who sent me to the U.S., who took a quiet pride in what I could become. Maybe that was the real bond—the recognition, even when words failed.

Three days after leaving Houston, and finally having secured a passport, I found myself sitting in the Frankfurt airport during a layover to Tehran reading a not-so-interesting book I had purchased at one of the National Museums during my DC stay. Because, well, I’m a bookworm and empty time is just time for reading.

I was half-heartedly reading my book when I suddenly noticed a young, energetic Iranian woman taking a seat next to me. There are a lot of empty chairs everywhere. This is not a good time to chat me up, lady. I’m pretty moody. “Salaam! Are you also going to Tehran?” she said enthusiastically in Persian.

“Yes. Banafsheh, nice to meet you,” I introduced myself also in Persian, mustering up a half-hearted smile.

“I’m Nargess. Good to meet you too.”

I set my book down on one of the small side tables next to the stark black airport chairs and turned my attention to Nargess, who began to animatedly recount her wild escapades in Germany.

“You see this carry-on?” she asked suddenly. I looked over at the small trolley-looking bag beside her—it reminded me of the kind old ladies use for grocery shopping.

“Yeah,” I said, intrigued.

She leaned in and whispered, “I’ve stuffed a bottle of champagne in the very bottom.”

I was struck by her fearlessness, her mischief. Once again, I found myself marveling at the spirit of Iranian women—how we learn to resist in the smallest, most ordinary moments. Alcohol was banned, the risks real, and yet here she was, casually planning to stroll through Mehrabad International Airport with a bottle of champagne tucked into her carry-on. She was visibly vibrating with defiance. It was inspiring. After nine years in the U.S., I had forgotten the thrill of everyday resistance. She was reminding me of a part of myself I hadn’t felt in a while—the risk-taker, the rule-bender, the girl who didn’t wait for permission.

Then the speaker crackled on, inviting us to line up for boarding. I stood up, distracted, still staring at her carry-on, trying to see if the shape of the champagne bottle was visible through the contours of the bag. In the moment’s rush, I left the book I was planning to read behind on the end table.

Nargess and I said our goodbyes only to be reunited at our seats once inside the plane. Our assigned seating was one seat apart from each, separated by the aisle. The airplane was one of those 2, 5, 2 seats-per-row models and we were seated on the right side of the plane and on the very first row of the economy section. I was in the window seat, at the end of our row, she was at the end of the 5-seater column.

“What are the odds?!” “How did this even happen?!” We kept repeating while talking past an older gentleman, a medical doctor, who was sitting between us and quickly losing patience with our chattiness.

“Would you like to switch seats with me?” the doctor finally asked me, clearly annoyed but trying to remain polite.

“Yes, thank you! So kind of you.” I said feeling a bit guilty for being inconsiderate. I got up to switch into my new seat.

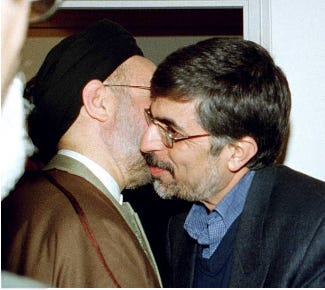

I plopped down into my aisle seat and noticed that the usually closed curtain between economy and business– jealously guarded by the flight attendants–was left open. While the overhead lights were still on in economy, business class had already gone dark. Just as I looked through the crack, registering my extra access, I saw Gholam Hossein Karbaschi, the mayor of Tehran, walk in and take his seat. He must’ve been one of the last few to board; we’d all been seated for a while. He lingered before sitting, perhaps placing something in the overhead cabin, giving me just enough time to make sure it was him. A Lufthansa flight attendant caught sight of my stunned expression and quickly drew the curtains shut, as if to shield the elite from the economy gaze.

Too late, lady. Curtain or no curtain, someone from the unwashed masses got a peek into the other side. And that was all I needed to activate. It was absurd. Perfect timing and a perfectly placed crack in the wall had let something through.

Karbaschi was, at the time, probably the most well-known and well-liked regime operative among Iranians inside and outside the country. Although a former cleric, he had given up the robe to become a technocrat and was responsible for some major changes in the Capital city and a large majority of the public loved him for it. “Finally,” one would often hear during those days, “someone who is working on our behalf.” A leader who was known for rooting out corruption, Karbaschi had also started the first Iranian full-color newspaper, Hamshahri, which was directly connected to the mayor’s office.

On Fridays, Hamshahri published translations of political theory texts by thinkers like Habermas and Derrida, alongside essays by Iranian reformist philosophers and clerics. The mayor’s newspaper—and others like it—were effectively putting Western critical theory and Islamic thought side by side, distributing them to newspaper stands on street corners across the country for public consumption.

This wasn’t just symbolic. These papers made it possible for Iranians to imagine a different kind of political Islam, a different kind of Islam from the one they were experiencing, one that wasn’t focused on their private choices—one that could be questioned, challenged, even transformed. Change wasn’t just an abstract idea; we saw it unfolding in real time through public debate.

As the mayor of Tehran, Karbaschi was known for bulldozing apartment buildings and office buildings built without city approval, removing tired and outdated revolutionary slogans and propaganda from walls, planting thousands of trees, banning much of the private traffic in central Tehran, opening more than a hundred parks and tearing down the walls that kept many of the already present parks from being enjoyed by the larger public. In the process, Karbaschi also angered the bazaar merchant class by raising taxes, earning him the reputation, during his time as mayor, as "the most loved and hated man in Tehran."1

As I already mentioned, the mayor was also a key supporter of Mohammad Khatami's first presidential election campaign. Word on the street was that Khatami owed his landslide victory, just a few months prior, to the mayor.

Here I was, landing in Tehran during an especially charged period of struggle within the political establishment between the reformists and conservatives.

The reformists were committed to resolving the inherent contradictions in trying to extract a democratic, modern political framework from an autocratic constitution. There was plenty of philosophical and theological gymnastics involved, and many of us wanted to believe a break was possible—without another revolution. The public, still bruised by the last one in 1979, was wary of risking everything and failing again.

We also hoped that the critical discourse unfolding in papers like Hamshahri would seep into the broader public narrative, sparking a movement that extended beyond the literati and student circles.

Karbaschi was one of the key architects of that hope.

It took me a few minutes to contain my excitement. I caught Nargess’ eyes and signaled for her to lean towards me across the aisle.

Trying to contain my shock, I whispered: “Gholam Hossein Karbaschi just entered the airplane.”

Continue reading, the next part is already available.

https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/01/world/the-case-of-the-teheran-mayor-reform-on-trial.html

So good! 💖