Previously: In a bold, half-baked move, I asked Iran’s most enigmatic mayor for permission to make a student film about him. And, to my astonishment, he said yes. "My assistant will call you." The "yes" allowed for more than access; it offered me a way back into a country I had long felt exiled from. That night, I lay awake unsure if the promised call would come, but certain of one thing: I was no longer just watching history unfold—I had stepped inside it.

Read the previous post by following the link below.

“Banafsheh! Banafsheh! Wake up! Someone from the mayor’s office is on the line!” My mother’s voice yanked me out of a deep sleep.

“Chiye?! Che khabare?! (What?! What’s happening!?)” I echoed her near-panicked tone, my half-asleep mind still a blank slate.

“It’s Karbaschi’s assistant. He’s on the phone, waiting for you. Get up, deegeh (a term used for emphasis in Persian)!” Her voice was impatient, but her face was lit with a stunned smile, eyes twinkling in disbelief.

I sprang up from the makeshift bed on the floor and stumbled toward the phone.

“Alo?” I said, clearing my throat.

“Sobh bekhayr khanum-e Madaninejad. Inshallah ke khoob hasteed o mozahemetoon nashodam. Tehrani, dastyaar-e aqa-ye shahrdar hastam. (Good morning Ms. Madaninejad, I hope you’re well and that I haven’t disturbed you. My name is Tehrani and I’m the Mayor’s personal assistant.”

“Sobh Bekhayr (Good morning) Mr. Tehrani and many thanks for contacting me as promptly as you have,” I said.

Social theory wasn’t on my radar back then, but even without it, I could sense that the terrain of gratitude was a difficult cliff to navigate. Too much, and I might come off as unworthy. Too little, and I’d risk sounding entitled.

Now I know that gratitude is not neutral—especially for anyone navigating asymmetrical power structures. As Sara Ahmed writes in The Cultural Politics of Emotion, gratitude is often expected from those receiving institutional or interpersonal “kindness,” particularly when they lack formal power. It becomes a performance—demanded rather than offered—more about affirming someone else’s generosity than expressing one’s own truth.1

Thankfully, sometimes there isn’t time to stage the performance. Instinct takes over. Working with Karbaschi was one of those times. I had no social script for such an encounter, so what came through was unscripted and real, a version of me that wasn’t calculating tone or effect, which turned out to be the most honest and effective one.

These days, the aim is to prepare as much as I can—and then trust that instinct. Those relational practices. The instinct I’ve been unwittingly honing for decades but still struggle to trust—because I didn’t learn it from a book. Trust that it will rise, unconsciously and somatically, to meet the moment and carry me through.

“The Mayor said that you are interested in making a film about him. I’m reaching out to let you know that he’ll be riding his horse close to the Karaj dam tomorrow morning at 7 a.m. and would like for you to be present,” Tehrani said, sounding very official.

“That’s wonderful, please thank him for the invitation. I will be there. Could you share the exact location please?” I said with a gulp, realizing that I had less than 24 hours to find professional camera and sound equipment.

“I can personally give you a ride to the location,” Tehrani said, before giving me the pickup details. For security reasons, I don’t think driving myself to Karaj was even an option.

“Yes, that sounds very helpful, thank you,” I said.

We said goodbye and hung up.

I sank into the seat next to the phone, still reeling from the call, and caught sight of my mom. She was frozen a few meters away, staring at me in disbelief.

“I thought you were kidding last night,” she said, a bit embarrassed.

“Listen,” I said feeling numb, “don’t feel bad. I wasn’t sure it had all happened either.”

The rest of the day was a scramble for equipment.

A few more unlikely coincidences later, I’d found everything I needed.

The next morning was a Friday, the national sabbath. I walked the early dawn deserted streets and showed up at an office near Vanak Square—not far from our apartment—with the equipment hanging off my shoulders. Feeling a bit unsafe, I rang the bell to what looked like a residential apartment. Mr. Tehrani opened the door promptly, his demeanor appearing a bit too serious for the occasion.

He was a relatively good-looking man in his early thirties. As I placed my equipment on a desk near the entrance, I noticed a photo of him, tall and stocky, standing beside his wife and two kids, looking every bit the dedicated family man. The picture had a calming effect. He caught me looking at the picture and said the names of his children out loud. It was an awkward meeting for both of us, and he wanted to highlight the professional nature of it to reinforce propriety.

After a few moments, Tehrani picked up his bag, offered to help carry my equipment, and escorted me to his unshiny Toyota, parked directly across the street.

In the car, he spoke at length about his wife, her job, and the challenges of being a good father, all of which put me further at ease. We were headed toward the Karaj Dam, located 63 kilometers northwest of Tehran. It was a national monument—Iran’s first multi-purpose dam—and I was excited to see it for the first time.

The conversation turned to the challenges of making a living in Iran, and despite being a government employee, Tehrani wasn’t shy about getting political. The culprit, he said bluntly, was the conservative establishment.

“It has to go.”

Soon we were talking about immigration and my life in the United States. He was eager to emigrate with his family and mined me for insider information. I was more than happy to share what little I knew, given that our circumstances were worlds apart. Over the following months, as I met more people in the Mayor’s office, I found that emigration was a recurring theme. The youth were especially hopeful about the promise of reform, but they weren’t naive. In this land of hustle, everyone had a backup plan for their backup plan.

I learned that the horse Mr. Karbaschi was riding had been a gift from Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the two-time president of the Islamic Republic (1989–1997) and a man often dubbed Iran’s kingmaker. Rafsanjani had always maintained a special relationship with the Supreme Leader and liked to play both sides. I was thankful that he appeared more aligned with the reformists—for now.

We arrived to find Karbaschi galloping his horse like a seasoned rider, and it completely threw me. Here was a former cleric, a key figure in a regime supposedly fighting westernization, riding like he was out for a frolic in London’s Hyde Park. He wore what looked like brand-new flared-hip black and brown breeches, tall shiny black boots, and a black velvet riding cap. The most enigmatic political figure in Iran was dressed in full English riding gear. Was this irony, audacity, or both?

I spent the rest of the morning chasing him on foot, a giant camera on one shoulder and sound gear on the other, stumbling through the valley like a one-woman film crew. I barely knew what I was doing and had to stop often just to catch my breath. This is not how this is supposed to be done, I kept thinking between sprints, trying to keep up.

“Hey, you made it!” Karbaschi finally stopped to say hello.

“I did! Beautiful horse!” I managed to say, breathless from the chase.

It was a cold October morning, and I had a few layers of clothing—my breath visible in the frigid air, my body caught between sweating from the effort and shivering now that I had stopped.

Then, without warning, he flashed a naughty grin in my direction and took off again. That was my cue to start running again. I could just hear the conversation with his reformist buddies later that day: “NASA girl came all the way from America just to chase me on foot through the valley.”

I filmed him a few more times during that trip.

On April 4, 1998, shortly after meeting him on the plane, Karbaschi was arrested on trumped up corruption charges.

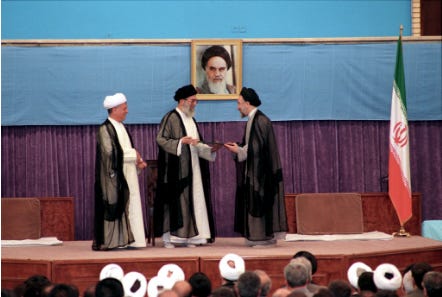

Karbaschi’s trial was widely seen as the most prominent move in a conservative campaign to undermine the reformist administration of President Mohammad Khatami. Led by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, Iran’s clerical conservatives claimed they were exposing financial corruption, but it was clear to most observers that the real aim was to weaken the reformist surge. The trial became a spectacle, often devolving into heated arguments—sometimes outright shouting matches—between Judge Gholam-Hossein Mohseni-Ejehei (currently Iran’s Chief Justice) and Karbaschi, who held the same clerical rank. It drew record audiences on national television and was dissected in detail by the Iranian press.2

“Despite last-ditch efforts by his supporters”3 including a petition “signed by more than 130 members of parliament—nearly half the chamber” Kabaschi began serving his two-year sentence in May 1999.4

Finally, in January 2000, Khamenei agreed to decree his amnesty.

I visited with Karbaschi during the trial and again after his release from prison.

But that’s a story for another time.

What mattered most was already behind me, stitched together in small moments that only made sense in hindsight, many years later.

Make sure to tune in for Part 8 when I bring together all the threads of the 7-part story.

Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 2nd ed., Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

https://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/01/world/the-case-of-the-teheran-mayor-reform-on-trial.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/05/09/world/iran-s-ex-president-backs-a-jailed-aide.html

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/336541.stm

I can't wait! <3