An Architecture of Connection - PART 1: The Signal and the Summons

A nonlinear memoir about grief, the former mayor of Tehran, and the moments that quietly rearrange everything

I’ve told this story at dinner parties before—the time I flew to Tehran during a family emergency and somehow, through a strange choreography of chance, grief, and sheer audacity, ended up making a student film about the most powerful man in the country. I usually tell it with a smirk and a well-placed pause, like a good party trick.

But the truth is, something else was happening underneath it. This wasn’t just a wild coincidence or a lucky break. It was the first time the world revealed itself to me as alive—responsive, uncanny, interconnected. I didn’t have the words for it then, but now I know: I was brushing up against the architecture of connection. And once you see the pattern, you might push it to the background and overlook its significance—but you can’t unsee it. Maybe it’s something we all brush up against, now and then. A field. A current. Something that doesn’t speak in words.

To understand why meeting Gholam Hossein Karbaschi–who was at the time the most beloved reformist in Iran–felt like stepping into something bigger than myself, it might be helpful to share what was happening in Iran at the time.

Between 1991 and 2009, the country was gripped by a reform movement—especially during the two years I ended up working with Karbaschi. The reform project ultimately failed, but it was a necessary stepping stone towards a working political philosophy for the country, which is still waiting to be born.

During those years, I broke bread with, studied, interviewed, wrote about, and made documentary films about the reformists. Ultimately, like most critics of the regime, I came to the conclusion that there can be no transition from authoritarianism to democracy in the Islamic Republic of Iran where the faqih (religious jurist or ayatollah) has absolute power.

The reformist thinkers couldn’t philosophize the country out of an authoritarian constitution–they tried. And the voters couldn’t vote their way out of one either. In his first presidential run, Mohammad Khatami, campaigning on liberalization and reform, inspired an 80% voter turnout, with 70% supporting pro-democratic, reformist candidates.1 "Even in Qom, the center of theological training in Iran and a conservative stronghold, 70% of voters cast their ballots for Khatami.”2 The issue was and remains the same, however. The political philosophy of the Islamic Republic, the Velayat-e Faqih3 system, is founded on the absolute authority of the clerical establishment and its highest jurist, the Supreme Leader. This structure effectively places their power above the will of the people.

I spent years studying the reformists for my graduate work, but it all began when I accidentally met Gholam Hossein Karbaschi, the former mayor of Tehran and arguably the one who started it all. Karbaschi is credited with helping to get Mohammad Khatami elected as president and, in doing so, bringing the reformist movement into the political arena.4

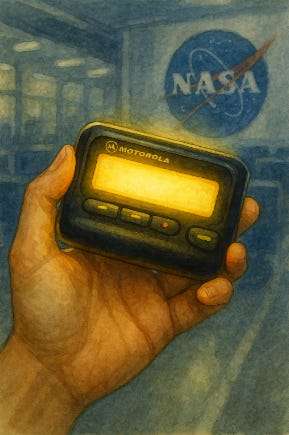

It was October, 1997. I was on the 4th floor of the Mission Control building at the Johnson Space Center in Houston TX when I got a page from my brother in Tehran: “Urgent, call me now.”

If you come from an immigrant family, you know exactly what a frantic message from the mother country does to your nervous system. My first instinct was to walk to the landline in the coding pen where we were all busy making a deadline for the next Space Shuttle launch and call Tehran.

“Hey, can I make an international call from this phone?” I turned towards the room and asked no one in particular. We didn't call them landlines by the way; they were just phones back then.

“Yeah, I think there is a phone in the command center,” the sweet white-haired old-timer whom we called Santa said. Santa owned a Christmas tree farm, which was all he could talk about during the festive season.

“But umm,” he paused, looking uneasy for prying, “where do you want to call, Banafsheh?” probably guessing that I wanted to call back home. Sure, it was pre-9/11, but even then, calling Iran from inside Mission Control felt like a fast track to ending up on someone’s watchlist.

“You might wanna call your manager before making that phone call, dear. Just to cover your ass.”

I called Don Pitman, who felt more like a father figure than a manager. “Don, I got an emergency page from my brother back home. Is it okay if I make a quick call to see what’s going on?”

“Of course,” he said, his voice as calm and kind as ever. “Call me back and let me know what’s going on, okay?”

“Thanks, will do,” I said, hung up and called our house in Tehran. It was late at night there and my brother, who was probably waiting by the phone, picked up after the first ring.

“Salaam Kayvan jaan, chi shodeh? (Hi dear Kayvan, what’s going on?), I said, trying to remain calm.

“Look, he’s okay now, so don’t get alarmed, but Baba has had a heart attack. He’s in the hospital. I need maman to come home,” he said quickly, with a voice that sounded extremely controlled and rehearsed. My brother, who was 21 at the time, was understandably way over his head and wasn’t mincing words.

That one phone call set in motion a series of events that led to me filming the mayor of Tehran a few days later, and got me brushing up against a kind of knowing I had not come into contact with before.

But first let me rewind the story just a bit further to start with how an Iranian young woman, fresh out of college, got hired by a couple of Texas good ‘ole boys to help build the Graphical User Interfaces for the new Mission Control Center in Houston.

Continue reading the series. The second part is already available.

In the Iranian presidential election held on May 23, 1997, Mohammad Khatami secured a decisive victory with 69.1% of the votes. The election saw a high voter turnout of 79.92%, with 29,145,745 ballots cast out of 36,466,487 eligible voters. Source: https://irandataportal.syr.edu/1997-presidential-election.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/tehran/inside/elections.html

The Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist—or Velayat-e Faqih (ولایت فقیه)—is a 20th-century concept in Twelver Shia Islamic law which holds that, until the reappearance of the "infallible Imam" (the Mahdi), the religious and social affairs of the Muslim world should be administered by righteous Shi'i jurists (faqih), led by the most senior among them: the Vali-ye Faqih. This doctrine, now the cornerstone of the political philosophy and constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), was developed and popularized by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the IRI and its first Vali-ye Faqih—also referred to as the Supreme Leader in the Constitution. The position is currently held by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

In 1997, Mohammad Khatami, a relatively unknown Shi’i cleric, ran for president on a platform of liberalization and reform. During his election campaign, he proposed the idea of Dialogue Among Civilizations as a response to Samuel P. Huntington's 1992 theory of a Clash of Civilizations. The United Nations later proclaimed the year 2001 as the Year of Dialogue Among Civilizations, based on Khatami's suggestion. During his two terms as president, Khatami advocated freedom of expression, tolerance and civil society, constructive diplomatic relations with other states, including those in Asia and the European Union, and an economic policy that supported a free market and foreign investment.

i cannot wait for the next installment!

Love it and love you, Banafsheh