Before jumping into Part 2, I want to thank those of you who read and shared Part 1 of “Monsters Under the Stairs.” Writing this story has been a process of excavation—of memories long buried and emotions still raw. What follows is one of the most difficult moments of my childhood. A moment I had forgotten about, until I was in my late 20s. I share it not just as personal history, but as a reminder of what so many have endured under this regime. If you missed Part 1, you can find it here.

We made an unexpected sharp turn before reaching the gate, right into the prayer room building. Mostajabian directed my body into the tight space underneath the staircase, filled with extra furniture. It smelled like years of caked dust. The lights were off. What was their plan in this dark space? I could sense that Ms. Husseini, my kind, smart and open-minded former confidante, was uncomfortable. Seeing her discomfort and feeling claustrophobic under the stairs brought the situation home and butterflies were starting to wreak havoc in my belly. I was finding it difficult to breathe. Still, I kept my eyes defiant, projecting disgust and ridicule for the authority the other two had not earned. I hated Mrs. Mostajabian with a passion, and I let it show. What bullshit are you going to heap on me now, I communicated through my eyes. What cruel, irrational game are you going to play with me today?

Mrs. Mostajabian gave me time to get good and scared in the silence. We continued to play our usual game of glare and smirk. Ms. Husseini, my old friend, nursed a genuinely worried look, and the Ice Queen was indifferent as always. Mostajabian finally broke the silence without mincing any words. “Have you been noticing lately how some of our students at the school have gone missing?” She spoke slowly and savored every word in her mouth as if it were aabnabaat (hard candy). I half expected her to unwrap a real one and offer me a piece, just to complete the horror show. My heart stopped.

These were dangerous years for politically active kids in Iran.

I had intentionally stayed away from dissident recruiters; their language was not convincing. Why is she telling me this? Do they think I’m political?

Early in 6th grade, year two of the revolution, an official-looking lady had visited our classroom, taking time away from our annoyed Social Studies teacher, Ms. Rezazadeh. She invited us to ask her any questions we had. “Anything, anything you have questions about, lay it on me. Go ahead. I am here for you. I know it must be a confusing time.”

It was a confusing time.

On TV, I had watched a kangaroo court session the regime was holding for the leaders of the Tudeh Party—a communist political party affiliated with the Soviet Union—a few nights before her visit. They used the word communist in the courtroom, a word I had been hearing a lot. I was curious to know what it meant. My parents weren’t interested in politics, so after a long pause, I raised my hand and earnestly asked "Ms., I have a question. What is communism?”

An immediate hush fell over the classroom. The silence was so tight, it felt like it might snap at any moment. I turned to look at Ms. Rezazadeh for a lifeline: what did I say wrong? I liked and trusted Ms. Rezazadeh. She had a look of initial horror, which slowly morphed into, “For the love of God Banafsheh, are you really this naive?” and landed eventually on an expression of heartbreak. This was a school where real questions could never actually be asked and any assurance of safety was only ever a trap.

“I’m sorry, WHAT did you say?!” said the cutesy, ask-any-question lady with a heavy heap of cruelty. I was beginning to feel the sting of having been played, her stare growing sharper with each passing second. Her eyes widened in disbelief, her head tilting to the side as if trying to contort itself into a question mark.

I was annoyed that she had the gall to be angry at me after betraying my trust while trying hard to not sound offensive. "I said, I was watching a court proceeding last night and the word Communism came up a lot. I don’t understand what it means. You invited us to ask any question, so I’m asking you what it means,” I explained wanting to close the loop on the confrontation unapologetically.

Her eyes widened even further and her face looked flushed. Most noticeably. there was fear in her eyes, fear that if she didn’t perform an adequate amount of disgust for my question in this public space, word would get out to her superiors that she might be a communist sympathizer herself. “Don’t ever repeat that word again! Do you hear me?! Ever!!” she said almost screaming. She took a second to catch her breath. “They don’t believe in God. And that’s all you need to know about that.” She was quite shaken up, muttered a stiff goodbye, and left in a flurry, her lips pursed so tightly it looked like they might vanish. Afterward, we looked back on the whole incident—not just as something tense and frightening, but almost like a dark comedy skit. Never had the regime’s fragility, and the absurdity of their version of Islam, been more evident.

When I got home from school, I could hear my parents whispering in the kitchen as I arrived in the living room.

Oh shit!

“Banafsheh jaan (dear), can you come here for a sec, please?” my dad said. “Yes?” I said softly as I peeked my head into the door, my body unconsciously lagging behind the wall for safety. I have ruined something again by being me. “Did you tell someone at school that we were communists?” he asked, with an unusual amount of tenderness. My heart sank. “No!” I said and proceeded to tell them the story.

“Look, azizam (my dear),” my dad said, “don’t ever, under any circumstance, say anything about anything that happens at the house to anyone at school again. Do you understand what I’m saying?” Despite the emphasis on certain words, his eyes and voice were uncharacteristically gentle. My parents were under a lot of pressure in those early years after the revolution and my dad, especially, was really short-tempered.

But I had just asked a harmless question. “Okay,” I replied. What does this mean? Can I never ask questions at school? What is the point then? Years later, my father told me that it was on that day that he realized he would have to get me out of the country before something really bad happened.

A few weeks later, I found a copy of the Communist Manifesto in an English language bookstore in Pardis Square, close to our apartment. Bookstores that carried foreign language books were not fully “cleansed” after the revolution. I brought the book home but couldn’t get past the first few pages; the English was too advanced. What I did understand from the book was the message that the history of all existing societies is the history of class struggle, and that Marx and Engels were inviting the workers of the world to unite and overthrow the oppressor, owning class. Weren’t these central tenets of Ayatollah Khomeini’s platform?

I couldn’t wait to unravel these mysteries but didn’t know how to. It was too dangerous to ask questions, too dangerous to create and perform plays during recess, too dangerous to talk about philosophy, too dangerous to listen to music, too dangerous to watch films. I remember my friends and I having conversations about how everything had been made officially or tacitly illegal. We would mentally tally the few remaining legal activities: blinking? Standing still? Breathing? Talking to each other during recess? Maybe? Every day we wondered if chatting was still allowed, but we figured we’d find out the hard way. We joked about adding ‘existing’ to the list of allowed activities, but decided they just hadn’t gotten around to banning that yet.

During this time, kids my age were being apprehended for political work and consequently disappeared. I had noticed students missing from our classrooms. The students shared guarded murmurs about it during recess and lunchtime.

The regime was decapitating the resistance and children were fair game.

When, in 1988, the regime extrajudicially executed thousands of dissidents, during what has come to be known as the 1988 Prison Massacres, some of them were children they had rounded up when I was in middle and high school. Tens of thousands of political and cultural prisoners in 36 cities were murdered: they were placed onto forklift trucks in groups of six and hanged from cranes every 30 minutes. Most were under 25 years old. (See Amnesty International’s report here)

Back under the stairs, Mrs. Mostjabian was a step closer to my face. “ARE YOU NOTICING THAT SOME KIDS ARE DISAPPEARING?” she asked again, this time much louder. I was frozen in place. I nodded my head, eyes wide with fear, trying to swallow the lump in my throat. I was genuinely terrified, and she could smell the fear. She smiled, proud that after almost two years of having me as a thorn in her side, the poison she had brewed up for me was having the desired effect. She hissed with a smile, “If you do not shape up, you will be one of those children who disappear. I’ll make sure of it, personally.”

I looked at Ms. Husseini, my former ally, but couldn’t catch her eye. Are you onboard with this, “friend?” I wanted to ask her out loud. Look at me! I wanted to catch her eye because seeing shame on her face could reassure me that one of these monsters still had some humanity left and maybe I didn’t have to lose the ability to trust people altogether. But she kept looking at her feet. There is no one who can help me. There is no one to trust.

The world changed color that day—everything took on a greyish hue. I set up an impenetrable, protective fort around me where I continued to reside for many years to come.

Soon after, I developed a duodenal ulcer and often stayed home sick. The plays during recess stopped and so did my senses of playfulness, defiance, and joy. Well, for a while at least. I was on time to school and started behaving. I looked at my feet during recess and my mother didn’t have to visit the office anymore.

Thankfully, mom did take me to see a young, gorgeous gastroenterologist who had just set up shop in Vanak Clinic after graduating from a school in the UK. I connected with Dr Fadaa’i immediately. I was drawn to anyone who smelled of the West, of what I considered to be freedom. After a regular health checkup, Dr. Fadaa’i asked my mother to step out of the office so we could have a private chat

I felt self-conscious being left with this movie-star-looking dude who was gentle, knew how to listen, and was looking at me with eyes that knew how to read between the lines. “You’re a rebel, aren’t you, Banafsheh?” the doctor asked, after studying me for a bit. “Umm… I guess?” I replied, feeling seen but shy. Being a rebel lives in the proximity of being special and I had been taught to feel ashamed of feeling special.

“So, how are you finding school?” he asked. Going to school had become extremely cumbersome and no one understood why I was suddenly resisting so much. Is he really asking me how I’m feeling? And just like that, I started crying and shrank in the office chair like a pansy wilting under intense heat. I shrank, in defense, because being vulnerable usually came at a price. He remained silent. “I’m dying,” I said without sounding dramatic. My tears had dried up. His eyes softened and he continued to just sit with me in silence for a bit longer. The school environment was as tough as any workplace at the time, and the public was aware of the repression children were enduring.

Many years later I realized that I didn’t say, “They want to kill me,” which would have been closer to the truth. I only said, “I’m dying,” because there was a third sentence Mrs. Mostajabian said to me under the stairs that day. “If you tell anyone,” she had warned me, “about what happened today, I will disappear you. Just remember, this meeting never happened." I don’t remember what Mostajabian said to me in Persian that day. Maybe I buried the words into the creases of my brain to make sure they didn't accidentally escape my mouth.

When my mom returned to the room, the doctor asked her to allow me all the leeway I needed, and most importantly, to not push me to go to school. God I loved than man.

Jahan Koodak Middle School tamed the girl they couldn’t control, but not for long.

Incidents like the one under the stairs wired the nervous system I carried with me to the United States after high school. I stepped into college, graduate school, teaching, and community and political organizing with a body that couldn’t trust easily, had difficulty extending grace, and was never fully settled. My nervous system was set on high alert—locked in a deep groove that, no matter how safe my surroundings, flashed the same warning in neon purple: You Shall Not Pass! You Shall Not Pass! Because a moat had been dug, a drawbridge has been raised, and a team of dragons had been hired for extra security.

It has taken me years to write this incident down. I say the words through tears and a shaking body while a trusted friend listens and takes them down lest I forget. I stop and chastise myself for getting emotional. I am alive and well, a middle-aged woman, living an enchanted life.

I think about what the girls and women are going through in Iran today, about all the girls and women the regime has killed, all the lives it has destroyed, especially during the height of Woman, Life, Freedom. I tell myself, as my chemistry teacher— whose name I have forgotten—used to say, “beel ro begzaar, kolang ro bardaar (time to put down the shovel and lift up the pickaxe)."

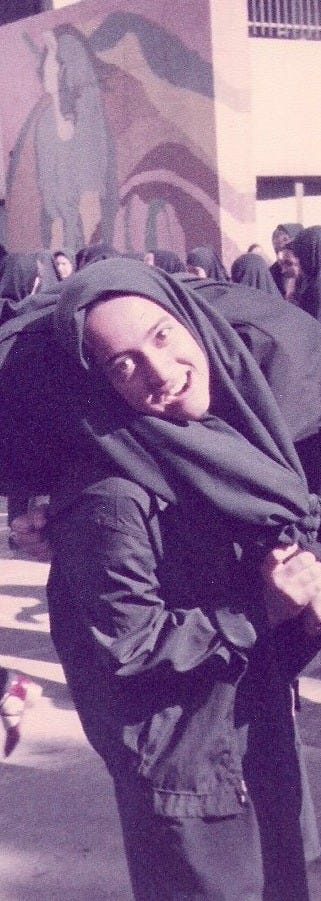

The Islamic Republic brings down its gavel on the bodies of every girl and woman. I resisted by jogging at 5:00 am when the security forces were asleep. They made running illegal for girls and women because they claimed it made our bulbous parts bounce and distract men from God’s work. I resisted by having bad hijab, by sitting on the windowsill of my friend’s car, screaming and singing at the top of my lungs in a country where a woman’s singing voice is banned, by moving through town delivering bottles of homemade wine to my friends, even though getting caught with alcohol was severely punished. When I was the last person in my middle school to change from a roosari to a maqna’e, when I created and directed defiant plays in the classroom, when I scoured the bookstores of Tehran looking for Harlequin and Barbara Cartland romance paperbacks—because, let’s face it, if I was going to live under tyranny, at least I deserved to know how scandalous hand-holding could be—when I finally found a European history textbook (a book that, at the time, I believed didn’t lie), when I attended secret mixed-gender parties and danced, when it stormed and I opened my window and sang Western pop songs at the top of my lungs—because, in case you hadn’t already guessed, pop songs were banned too—on every single one of those days, I was building and rebuilding myself, one defiant piece at a time.

My motto was “defeat under no circumstance.” Increase the pain, I can take it all. You can’t break me. This became my permanent modus operandi. No slight overlooked; no authority figure harmless enough to trust; no boy or man safe enough to let in. I reinforced the fortress around myself, ensuring that no mercy was offered and no grace extended.

Boy, am I thankful for my healing journey… Being that Banafsheh was hard as shit.

Sometimes I still hear her voice though, that slow, syrupy hiss under the stairs that conveyed the following message: “If you do not shape up, you will disappear.” Trauma doesn’t announce itself. It settles. In the bones, in the breath, in the spaces between words. And then one day, without warning, it speaks. I’m still working on molding and shaping it into gold. But I never did shape up—and I am still here.

I had tears in my eyes and whole body chills as I read your powerful words.

I read part 1 this morning, and came back to part 2 as soon as I could.

I saw a Woman, Life, Freedom bumper sticker while I was in traffic today. I live outside Nashville and I’d never seen one before.

This is one of those stories that’s going to stay with me.

Thank you for sharing. 🩷

wow, I knew you had a story behind the amazing woman you are. thanks for your eloquence.